What is gastroparesis?

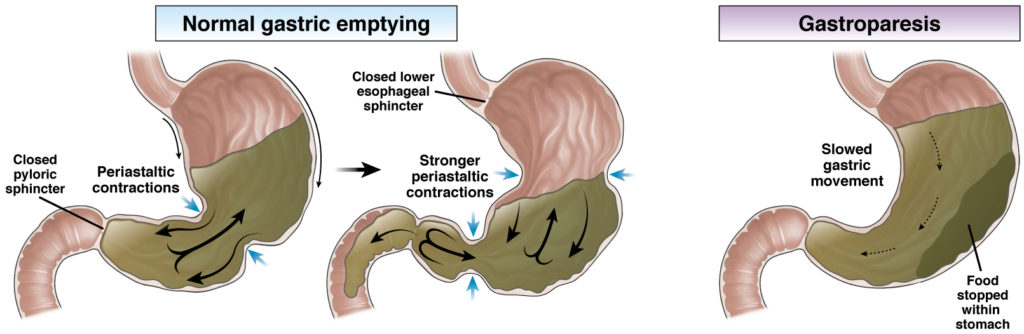

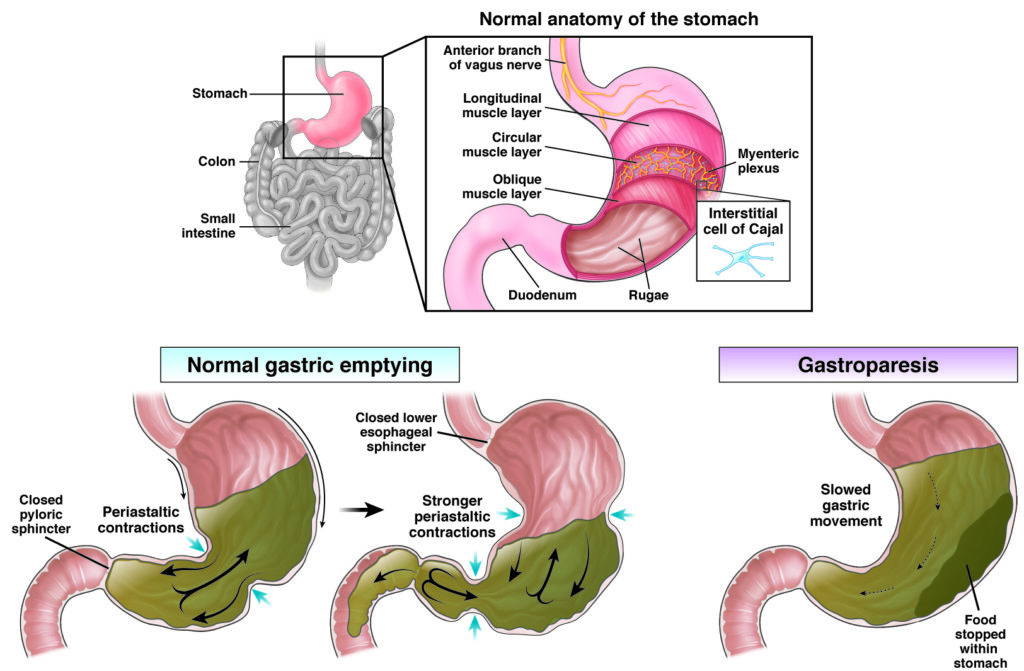

Gastroparesis is when the stomach has trouble clearing out its contents. It is also known as delayed gastric emptying.

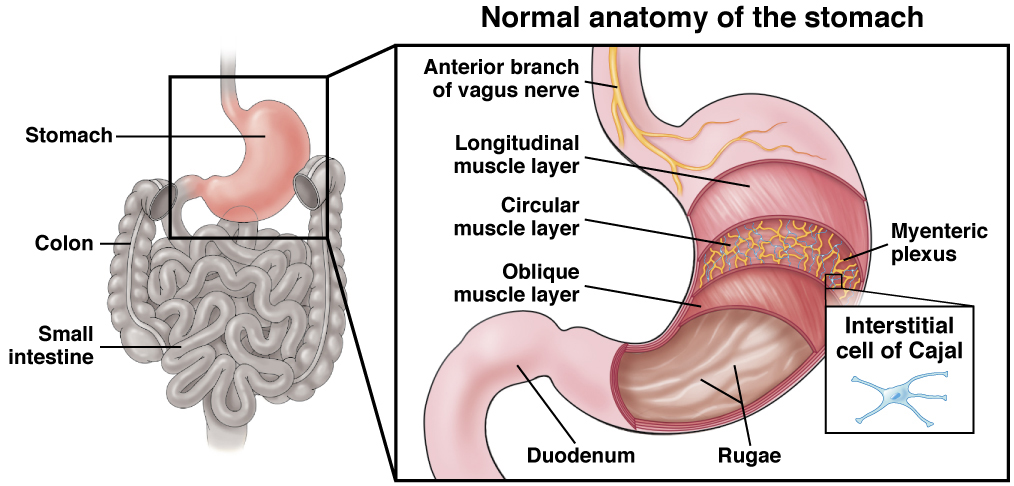

Food is moved within the stomach and out to the intestines through the action of muscles in the stomach wall. These muscles are under the control of the stomach’s own nerves and special cells called interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) as well as by nerves coming from the brain and spinal cord (the vagus and the sympathetic nerves).

In a person with gastroparesis, the stomach does not work the right way, so food moves slowly into the small intestine or stops moving in the stomach. This may be due to problems in the muscle itself, in the nerves or ICC.

Gastroparesis is not a mechanical block in the stomach.

Gastroparesis is generally found more in women than in men, although the reason for this is unknown.

Symptoms of gastroparesis

Symptoms are different for each person and can change in intensity and frequency over time.

Common symptoms of gastroparesis

- Nausea.

- Feeling full, even when eating only a small amount of food.

- Throwing up (often throwing up whole pieces of food that have not been broken down in digestion). Some patients can even identify food that they have eaten several hours (four or more) before.

Other symptoms

- GERD, also known as acid reflux. This can cause a burning feeling in the chest or throat known as heartburn.

- Pain in the upper part of the belly (abdomen).

- Losing weight without trying.

- Bloating (swelling, usually above the belly button).

- Not feeling hungry.

- Weight loss and nutritional deficiencies in severe cases.

Certain factors may make symptoms of gastroparesis worse:

- Eating greasy (high fat) foods.

- Eating large amounts of food with fiber, such as raw fruits and vegetables.

Causes of gastroparesis

Idiopathic gastroparesis

Gastroparesis can happen in anyone. In most cases, the underlying cause of gastroparesis is not known and the disorder is called idiopathic gastroparesis.

Diabetic gastroparesis

Gastroparesis is common in people with diabetes and roughly up to a third or slightly more of people with type 1 or type 2 diabetes may develop gastroparesis. When diabetes is the main cause of gastroparesis, it is called diabetic gastroparesis. People with diabetes have high levels of blood sugar, which can cause injury to the stomach muscle, nerves or ICC.

Other causes

- Problems from surgery done on the gut, which could result in vagal damage.

- Nervous system diseases, such as Parkinson’s disease or multiple sclerosis (MS).

- Medicine that blocks certain nerve signals to the stomach, particularly narcotics (opioids such as morphine, oxycodone, etc.).

- Rheumatological disorders, such as scleroderma.

Tests for gastroparesis

First steps include a physical exam, medical history and blood tests.

To confirm the issue is gastroparesis and rule out the chance that it is a block or structural problem, your doctor may also do further testing:

During the endoscopy, your gastroenterologist will use a long, thin (about the width of your little finger), flexible tube with a tiny camera on the end to look inside, going through your mouth. You will be given medicine to block pain and make you feel relaxed and sleepy, so you won’t feel much during the test.

With this test, you fast for eight hours and then swallow a special drink that makes it easier for food to show up on an X-ray.

These are tools to image the abdomen and see if other disorders such as gallbladder disease or pancreatitis could be the cause of the symptoms, instead of gastroparesis.

This is the best method for finding out how long a meal takes to empty from your stomach. You are given a test meal that has a small amount of radioactive material. It is then tracked by a radiologist using a special scanner, generally over 4 hours.

This uses a SmartPill, which is a small electronic device, shaped like a capsule, that you swallow. It records information as it moves through the digestive tract. It provides a different measure of gastric emptying that is not related to meals.

In this test you are also given a meal that is made of a special kind of material that contains a heavy form of the element, Carbon. When this meal enters the small intestine, it is broken down and releases this carbon in the form of carbon dioxide that comes out in your breath and this can be measure by special machines. The rate of generation of this carbon dioxide is dependent on how fast the meal empties from your stomach.

Treatment for gastroparesis

In most cases, gastroparesis is a chronic (life-long) health issue that cannot be cured. Symptoms of gastroparesis can come and go. However, there are many treatment options, based on how bad your symptoms are, to help you care for gastroparesis.

Talk to your doctor, especially if you have diabetes, about what treatments make sense for you. Controlling diabetes, if you have it, is one of the most important things you can do as a patient to improve your stomach function and symptoms.

- Stay away from or limit high-fat foods and foods that have lots of fiber, such as oranges and broccoli. These can be hard to digest. Chew food fully.

- Consider eating six small meals a day instead of three large ones. Eating less food may make it easier for the stomach to empty, because it is not as full.

- Seeing a nutritionist is an important part of the treatment and he or she can prescribe different kinds of diet depending on the severity of your symptoms. If symptoms are severe, a doctor may prescribe a liquid or puréed diet, because liquids empty faster from the stomach.

- Learn more about diet therapy for gastroparesis.

Metoclopramide is the only medication that is approved by the FDA for treating gastroparesis right now. It helps your stomach muscles move to help with gastric emptying. In addition, it works on the brain to suppress nausea. However, there are some risks to this medication, the most serious of which involve temporary or permanent problems with muscle twitching or spasms.

Erythromycin is an antibiotic that increases the movement of your muscles to help food move through your stomach. It may help some patients but the effects may wear off with time. Erythromycin can cause stomach pain and also interact with other medications that may effect your heart rhythm.

There are also other medications that may help gastroparesis symptoms, such as antiemetics (e.g. ondansetron or promethazine), which help control nausea.

Other drugs such as mirtazepine (an antidepressant) are also useful anti-nauseant drugs and can stimulate the appetite as well.

Ginger tea or other preparations may help relieve nausea. Some people also respond to acupuncture although there is as yet not enough evidence to be confident that it works.

For patients with severe nausea and vomiting that do not get better with changes to your diet or medications, a doctor may do surgery to put a gastric neurostimulator in your stomach, which is a battery-operated device that sends electrical impulses to the stomach muscles. There is no clear evidence for the effectiveness of this therapy and the FDA has only approved it on “compassionate grounds.”

When gastroparesis is very severe and the symptoms are not getting better with other treatment options, there are a few more options, only to be done if needed.

- A jejunostomy may be needed. Using surgery, a doctor puts a feeding tube into a part of the small intestine called the jejunum. This can be done surgically or endoscopically via the stomach, when it is called a PEG/J.

- Total parenteral nutrition (TPN), an IV liquid food mixture that is given through a tube in the chest, may also help. This may be used as a temporary treatment. The tube is put into the chest during a surgery.

There is no evidence for supporting the use of botulinum toxin injections for the treatment of gastroparesis.

Cutting the muscle at the pylorus (the junction between the stomach and intestine) is being performed at some centers both surgically and endoscopically but at this point is considered experimental with no strong evidence to support it.

If gastroparesis gets out of hand, it can cause:

- Severe dehydration or loss of water from the body (with vomiting that doesn’t stop).

- Esophagitis — pain and swelling in the esophagus (the tube that links the mouth and the stomach).

- Bezoars (a small mass in your stomach) that can cause nausea, vomiting, a block, or stop your body from using some medications the right way.

- Trouble controlling blood sugar levels in people with diabetes.

- Malnutrition, which can stop the body from getting the vitamins, minerals and nutrients it needs.

- Worsening quality of life — missing work and social events due to symptoms.