What is GERD?

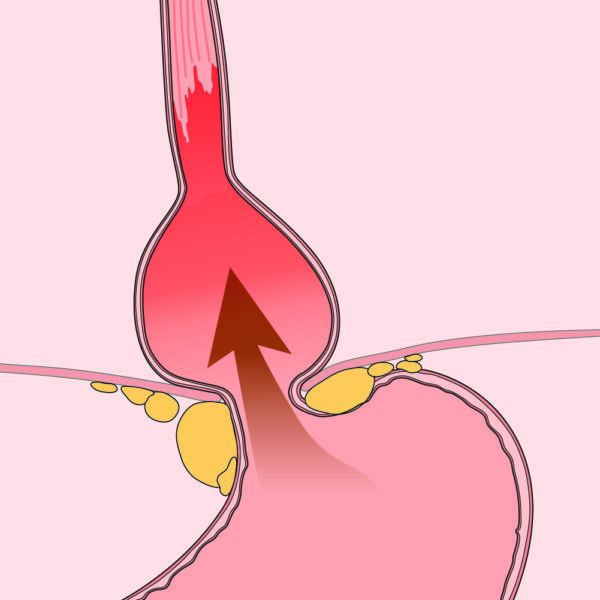

Gastroesophageal reflux, GERD or just reflux, happens when what is inside your stomach — stomach acid, food or other contents — backs up out of the stomach into the esophagus (the tube that links your mouth and stomach) and possibly all the way into your throat and mouth.

When that acid touches your esophagus (or what feels like your throat), it can cause a burning feeling in your chest or neck, known as heartburn.

Heartburn is the most common symptom of GERD.

Most of us will have occasional heartburn, but when your symptoms are frequent and bad

enough to impact your sense of well-being, it could be GERD.

While GERD is not life threatening, it can greatly lower your quality of life by impacting your

daily activities, your sleep and what you are able to eat.

Heartburn can often be avoided through changing certain habits (like when, how much and what

you eat and drink). Occasional heartburn can be treated with over-the-counter (OTC)

medication.

If symptoms don’t go away or get worse after a few weeks, talk to a gastroenterologist. You may

need some tests to rule out other health issues.

Note: Heartburn is not the same as dyspepsia (indigestion). Ask your health care provider for

more information on dyspepsia.

What are the symptoms of GERD?

Each person may not feel GERD in the same way.

Common symptoms:

- Heartburn – a burning pain behind the chest that may move up toward the neck. It can be

worse when you are lying down or bending over. Often happens after you eat. - Feeling like food is coming back up into your mouth, maybe with a bitter taste.

- Sore throat that won’t go away.

- Hoarseness (scratchy-sounding voice).

- Cough that won’t go away.

- Sore or burning throat that won’t go away.

- Asthma.

- Chest pain.

- Feeling like there is a lump in your throat.

- Pain when you swallow.

- Feeling as though food sticks in the throat when going down.

- Nausea.

- Frequent burping.

- Throwing up.

Alarm symptoms

Certain alarm symptoms may point to complications or life-threatening problems. Should you have any of these alarm-warning symptoms, talk to your health care provider right away.

- Chest pain with activity, such as climbing stairs.

- Losing weight without trying.

- Choking while eating or trouble swallowing food and liquids.

- Throwing up blood or material that looks like coffee grounds.

- Red or black stools.

Causes of GERD

Many things can cause GERD

Talk to your health care provider about what might be causing your symptoms.

Causes include:

- Being overweight, obese or pregnant.

- Some medications (talk to your provider and tell them exactly what you take).

- Smoking.

- Alcohol.

- Getting older.

- Some foods, how fast you eat and how much you eat.

Lower esophageal sphincter

You have a muscle, the lower esophageal sphincter (valve), which is found between your stomach and esophagus (the tube that links your mouth and stomach). If this muscle is weak or inappropriately opens, the valve does not work the right way and what is in your stomach can come back up (reflux).

Hernia

A hiatal hernia, which is a bulging of the stomach into the chest through the hole in your diaphragm normally occupied by the lower esophageal sphincter, can cause reflux. This condition is more common with aging and obesity. Hiatal hernias are very common. Most people who have hiatal hernia have no symptoms.

Getting tested for GERD

There are many tests for GERD but not all patients with heartburn or GERD need testing. Your health care provider may choose to do one or more tests to find out if GERD has hurt your esophagus (the tube that links your mouth and stomach) or is causing your symptoms.

Testing can also help your health care team guide your treatment.

Endoscopy with or without biopsy

An endoscopy is done to look inside your esophagus (tube linking your mouth and stomach)

and small intestine, and to do a biopsy (taking a small piece of the tissue to look at under a

microscope).

- You will be given medicine to block pain and make you feel relaxed and sleepy, so you

won’t feel much during the test. - During the endoscopy, your gastroenterologist will use a long, thin (about the width of your

little finger), flexible tube with a tiny camera on the end to look inside. - The tube is passed through the mouth into the small intestine as your gastroenterologist

does a careful exam. - Learn more about endoscopy.

Other tests may be performed in special situations or if symptoms are hard to control.

- Manometry checks if the valve between your stomach and esophagus that is meant to close after you eat (the lower esophageal sphincter), is weak.

- Manometry also checks to see if the rest of the esophagus is working the right way.

- You will be awake during manometry.

- During the test, a small, thin tube will be put through your nose and down your esophagus. This does not get in the way of your breathing.

- Once the tube is in place, you will be asked to swallow small amounts of water or gel as the machine records esophageal movements.

- This test is to find out if you have abnormal reflux and if reflux is causing your symptoms.

- It is very important to ask your health care provider what medicines you should or should not take before and during this test.

- The test goes on for 24 hours while you do your normal activities.

- This test is most often done in an outpatient center, often after an upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy.

- A very thin tube with recording electrodes on it is put through your nose and down your esophagus. You will leave your provider’s office with the tube still in your nose. You will return to the office to have the tube removed.

- The tube detects reflux and measures the pH (acid levels) in the esophagus and sends the data to a recorder that you need to carry with you.

- Keeping a diary of what you eat, when you eat and how you feel is very important during the test.

- This test is like the other pH monitoring test, except there is no tube coming out your nose and it can last more than 48 hours (or two days).

- It is very important to ask your provider what medicines you should or should not take before and during this test.

- During an upper GI endoscopy, your health care provider will attach a small capsule to the inside of your esophagus. This capsule will fall off on its own. You do not need to retrieve it.

- The capsule will measure the acid levels in your esophagus and send the data to a receiver that you need to carry with you for 48–96 hours.

- Keeping a diary of what you eat, when you eat and how you feel is very important during the test.

- Your provider will give you specifics on what to do.

- This test is an X-ray that takes pictures of the esophagus, stomach, duodenum and small intestine.

- You will need to drink a chalky liquid called barium while X-ray pictures are taken. The barium makes it easier for the health care provider to see.

- These pictures can be used to make a diagnosis and plan more specific treatments.

Treatments for GERD

Both medications and changes in your habits can put off and control symptoms of GERD. Talk to your health care provider about what choices are best for you to try first.

Keeping a diary about what you eat, when you eat, and how you feel after you eat can also help you better handle your symptoms and gives your health care provider useful information on what to suggest to make you feel better. Below is a list of things you can do to try to help control symptoms of GERD.

Daily habits to fight GERD

- Do not eat or drink items that give you heartburn or other bad symptoms.

- Be careful taking aspirin, anti-inflammatory and pain medications other than acetaminophen (like Tylenol®). These can make heartburn worse.

- Eat smaller portions of food during meals and don’t eat too much.

- Stop eating three hours before lying down to sleep.

- Raise the head of the bed four to six inches using blocks or phone books.

- If you are overweight, lose weight.

- Pressure on your belly can make reflux worse. Try not wearing tight clothing or control top hosiery and body shapers. Sit-ups, leg-lifts or stomach crunches can also make reflux worse.

- Stop smoking.

Foods that can cause heartburn

- Fried or fatty foods.

- Chocolate.

- Peppermint.

- Alcohol.

- Coffee (including decaf).

- Carbonated drinks.

- Ketchup and mustard.

- Vinegar.

- Tomato sauce.

- Citrus fruits or juices.

Medications for GERD

- Alka-Seltzer®.

- Maalox®.

- Mylanta®.

- Rolaids®.

- Riopan®.

- Tums®.

- Gaviscon®.

Side effects may include diarrhea (loose stool) and constipation (hard stool or trouble passing stool).

Available over the counter and in prescription strength. H2RAs reduce stomach acid and work longe,r but not as quickly as antacids. Examples are:

- Pepcid® (famotidine)

- Zantac® (ranitidine).

- Axid® (nizatidine).

Side effects may include headache, upset stomach, throwing up, constipation, diarrhea and abnormal bleeding or bruising.

- Prilosec® (omeprazole).

- Prevacid® (lansoprazole).

- Protonix® (pantoprazole).

- Dexilant® (dexlansoprazole).

Side effects may include back pain, aching, cough, headache, dizziness, belly pain, gas, nausea, throwing up, constipation, diarrhea.

Surgery for GERD

A small number of people with heartburn may need surgery because of severe reflux and poor response to nonsurgical treatment. Fundoplication is a surgery that reduces reflux. Patients not wanting to take medication to control their symptoms are also candidates for surgery.

Complications of GERD

If you have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), it is vital to work with your health care provider to take care of your symptoms.

If you are still having symptoms even after changing your diet or using medications, let your provider know. Your symptoms may not be from GERD or your may have a complication of GERD, such as:

Inflammation (swelling or irritation) in your esophagus (the tube that links your mouth and stomach).

This is when your esophagus is narrowed by ulceration and scarring. Strictures can make it hard to swallow, causing food to get stuck in the esophagus.

Such as asthma or chronic cough.

Barrett’s esophagus is a change in the tissue lining your esophagus that puts you at a higher

risk for esophageal cancer. Learn more about Barrett’s esophagus.

Reviewed by

Daniel E. Freedberg

Herbert Irving Assistant Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology, Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases, Mailman School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology, Columbia University, New York, New York

Daniel E. Freedberg

Herbert Irving Assistant Professor of Medicine and Epidemiology, Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases, Mailman School of Public Health, Department of Epidemiology, Columbia University, New York, New York